In a feat that could eventually unlock the possibility of speech for people with severe medical conditions, scientists have successfully recreated the speech of healthy subjects by tapping directly into their brains. The technology is a long, long way from practical application but the science is real and the promise is there.

Edward Chang, neurosurgeon at UC San Francisco and co-author of the paper published today in Nature, explained the impact of the team’s work in a press release: “For the first time, this study demonstrates that we can generate entire spoken sentences based on an individual’s brain activity. This is an exhilarating proof of principle that with technology that is already within reach, we should be able to build a device that is clinically viable in patients with speech loss.”

To be perfectly clear, this isn’t some magic machine that you sit in and its translates your thoughts into speech. It’s a complex and invasive process that decodes not exactly what the subject is thinking but what they were actually speaking.

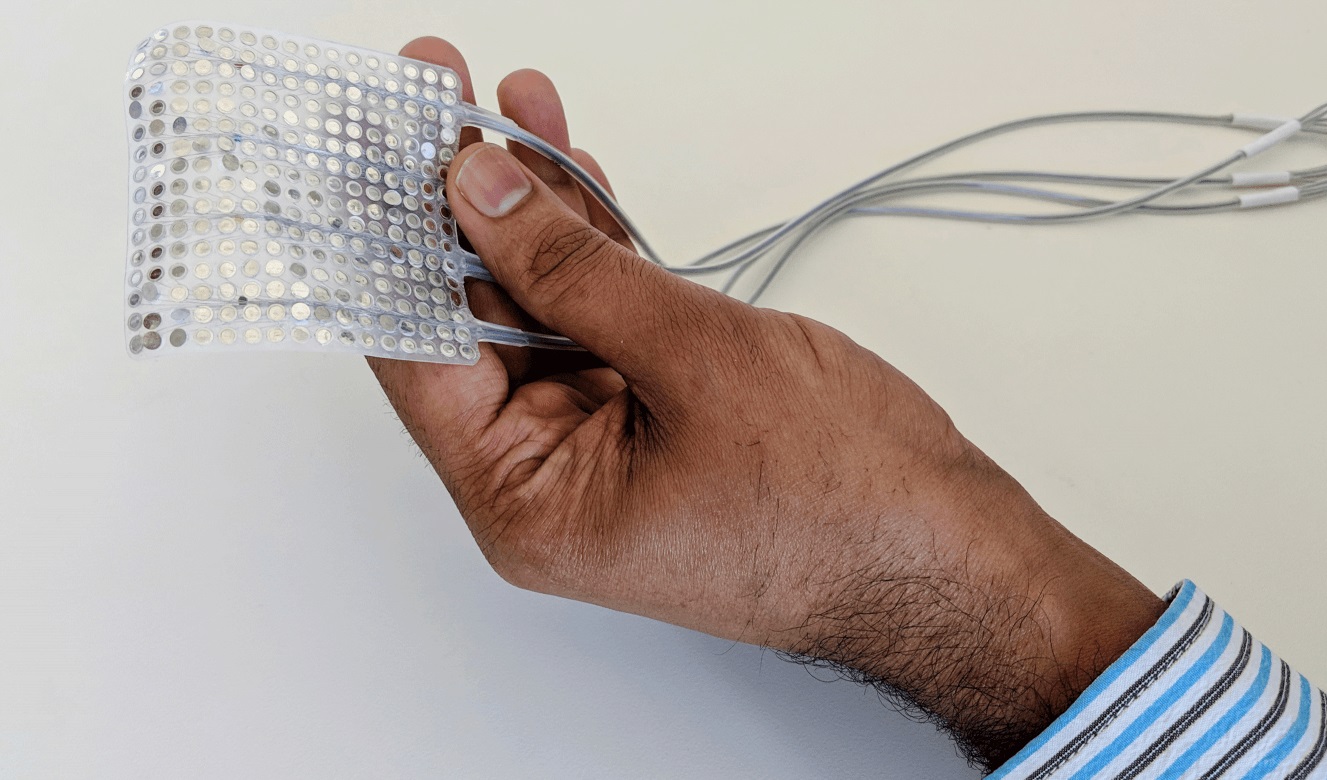

Led by speech scientist Gopala Anumanchipalli, the experiment involved subjects who had already had large electrode arrays implanted in their brains for a different medical procedure. The researchers had these lucky people read out several hundred sentences aloud while closely recording the signals detected by the electrodes.

The electrode array in question.

See, it happens that the researchers know a certain pattern of brain activity that comes after you think of and arrange words (in cortical areas like Wernicke’s and Broca’s) and before the final signals are sent from the motor cortex to your tongue and mouth muscles. There’s a sort of intermediate signal between those that Anumanchipalli and his co-author, grad student Josh Chartier, previously characterized, and which they thought may work for the purposes of reconstructing speech.

Analyzing the audio directly let the team determine what muscles and movements would be involved when (this is pretty established science), and from this they built a sort of virtual model of the person’s vocal system.

They then mapped the brain activity detected during the session to that virtual model using a machine learning system, essentially allowing a recording of a brain to control a recording of a mouth. It’s important to understand that this isn’t turning abstract thoughts into words — it’s understanding the brain’s concrete instructions to the muscles of the face, and determining from those what words those movements would be forming. It’s brain reading, but it isn’t mind reading.

The resulting synthetic speech, while not exactly crystal clear, is certainly intelligible. And set up correctly, it could be capable of outputting 150 words per minute from a person who may otherwise be incapable of speech.

“We still have a ways to go to perfectly mimic spoken language,” said Chartier. “Still, the levels of accuracy we produced here would be an amazing improvement in real-time communication compared to what’s currently available.”

For comparison, a person so afflicted, for instance with a degenerative muscular disease, often has to speak by spelling out words one letter at a time with their gaze. Picture 5-10 words per minute, with other methods for more disabled individuals going even slower. It’s a miracle in a way that they can communicate at all, but this time-consuming and less than natural method is a far cry from the speed and expressiveness of real speech.

Research heralds better and bidirectional brain-computer interfaces

If a person was able to use this method, they would be far closer to ordinary speech, though perhaps at the cost of perfect accuracy. But it’s not a magic bullet.

The problem with this method is that it requires a great deal of carefully collected data from what amounts to a healthy speech system, from brain to tip of the tongue. For many people it’s no longer possible to collect this data, and for others the invasive method of collection will make it impossible for a doctor to recommend. And conditions that have prevented a person from ever talking prevent this method from working as well.

The good news is that it’s a start, and there are plenty of conditions it would work for, theoretically. And collecting that critical brain and speech recording data could be done preemptively in cases where a stroke or degeneration is considered a risk.